Editor’s Note: Presented here are a video of Matt Stagner’s presidential address at the Association of Public Policy Analysis and Management’s (APPAM) Fall Research Conference and his remarks as prepared for delivery. The prepared text might differ from the speech in the video.

Thanks for the kind words, David. I’m not sure they are true.

And thanks to my Mathematica colleagues who have helped me put together these remarks. And to my family for coming from Chicago to make sure at least three people attend.

How many of you entered our field because you wanted to have impact on policy and practice? Me too! And today, I’d like to reflect on the connection of emotion, research, and policy.

After training, for years, and years, and years, and years... at some pretty highfalutin places, I was ready to have an impact on policy.

I worked for decades within and outside government, trying to make that impact. But even after being honored to serve this great organization in my current role, I’m not sure I’ve had the impact I had hoped for.

I’d like to talk with you today about why we may not, as a field, have the impact we wished for, and also how we may be able to do better.

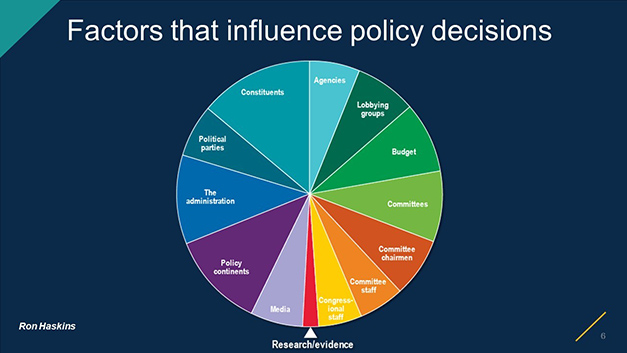

Ron Haskins, former APPAM president, has often presented this chart.

I love it. See that red sliver at the bottom. That is Ron’s estimate of the role that research and evidence have on policy decisions. We are the 1 percent! I hate being the 1 percent!

But so many other things (parties, constituents, lobbyists) truly drive public policy decisions. Though it’s not on Ron’s chart, I’d like to talk about the role of emotion in driving those things.

We certainly live in very emotional times. And policy issues may be more emotional than they have been in at least 150 years.

How does that make you feel? Sympathetic? Sad? Tense? Stressed?

We all feel something in response to stimuli, to our history, and to our environment. It affects how we take in and act on information and analysis.

Our craft may need to adapt better to this fact.

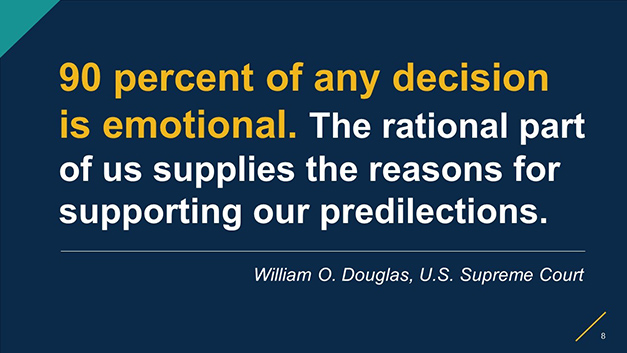

I’m not the first one to think of this, of course. I like this reflection by William O. Douglas.

I’m going to reflect on how that relates to APPAM members.

We try our best to be scientific. But perhaps that scientific distance gets in the way of our work having impact. Appropriate distance is certainly important for some of our work, such as rigorous impact assessments with funding consequences, but much of our work doesn’t require such distance.

We could get closer.

We could respond better to the emotional drivers of policy. I hope to convince you that we can do this, and that we can thereby increase our impact.

This evening, I’m going to tell a brief story from my own career. Mine is a story of failure but also of hope! I failed. I was a loser. But I think I learned from that failure.

My story is about child welfare, which focuses on the maltreatment of children and the placement of children in out-of-home care. It evokes many emotions.

But many other fields evoke strong emotions: health care (can I keep my doctor?), education (will charters undermine my public school?), crime (will my neighborhood be safe? Will people be treated fairly?).

I hope you can all relate to this story.

This is the story of a good evaluation that missed its target. It was rigorously designed and carefully implemented. But it in the end, it did not have the impact we had hoped.

Why?

Thinking back on it many years later, I think we failed because we failed to connect to the history and to the emotional perspectives driving the issues. We did not get close.

For context, let me take you back to the beginning.

Okay, this is pretty far back. And I wasn’t in the field yet when Moses was pulled from the river. But my point is that the history of child welfare goes back for millennia, including adoption and other forms of services. And it’s always packed an emotional punch.

The modern child welfare system in the U.S. can trace its roots to the progressive era. The emotional tensions around that time still linger with us. There are two powerful, emotional story lines in child welfare. And, sadly, they are at odds with each other.

One side is the desire to save children from the risk of harm. It is simply human to want to help a child in need. In the progressive era, this desire was epitomized by the so-called friendly visitors who helped, but also interfered with, the lives of immigrant and poor families.

It was also typified by the orphan trains that sent children west from large immigrant entry points, often separating siblings. Well-meaning upper-income people felt an emotional pull and wanted to save children from potentially dangerous situations.

That emotional desire to save children from potential harm touches us today.

Frequent news reports call out to blame the child welfare system for failing to protect children. Child welfare agencies are called to task for situations where they failed to remove a child or returned a child home only to find that the child was still in harm’s way.

So, that’s one side.

Child welfare has another, opposite, strong emotional pull: children being separated, perhaps unnecessarily, from their families.

People of color, new immigrants, and other vulnerable populations have always been at risk of losing their children to foster care or even the termination of parental rights and adoption. The state’s intervention to terminate parental rights is one of its most powerful and most frightening tools. People, rightly, get emotional about it.

The emotional pull is strong in two opposite directions. There’s a strong pull for us to reject the disruption of families by governmental authorities. But children are sometimes harmed by their parents.

Policy has vacillated. Back and forth, back and forth, reflecting the inherent contradictions in the system: protecting children from their families, and protecting families from undue interference.

How does policy research have an impact in such an emotional arena?

As the policy pendulum swung toward concern about unnecessary placement of children, family preservation services became a focus in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Family preservation services ask, is there something more that child welfare agencies could do for families when children face possible harm? Can we provide more and better services to keep families together?

They seek to get upstream and prevent placement of children away from their parents. And can we do that without leaving children in situations where they may be harmed? Without an emotional reaction from the child savers?

This focus on family preservation was happening when I was early in my career. Their expansion was fueled by federal funding. In 1993, I entered service in the federal government, joining the staff of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Entries into foster care were rising. Advocates for families wanted to see more done to help families and prevent these placements of children into care.

In response, Congress passed, and the president signed, the Family Preservation and Support Services Program Act of 1993. This bill doubled funding for “family preservation”, providing more block grant funds to states. And it, to the delight of policy researchers, required a rigorous evaluation. The task of designing that evaluation fell to me and my colleagues at the Department of Health and Human Services.

We examined a range of the most popular family prevention models, particularly the most popular model called Homebuilders. We picked a good contractor, and we sent them out to get it done under our guidance. All the best science was used. And I think we did great work.

We focused on a rigorous random assignment design to examine impacts of four programs. But we were scientists wading into an emotional swamp, without full awareness of the terrain.

The evaluation was scientific, rigorous, careful, and lengthy. It took years.

And it was not completed until well after I left the department.

The key findings: Not much worked. None of the four programs, in four separate states, showed statistically significant effects in preventing children from entering foster care. Placement rates were actually a little higher in the experimental groups, though not significantly so.

Advocates for family preservation were disappointed. And those concerned primarily with the safety of children suggested this showed the difficultly of such efforts.

But, frankly, few people paid that much attention.

What did I expect, as someone who wanted to make an impact on policy?

First, I thought maybe people would rethink their approaches to family preservation, redefining the program. A rigorous evaluation examined the most prevalent approaches and found that they did not have the hoped-for results! Wouldn’t people change? But the legislation and the guidance did not change significantly.

Second, I thought maybe there would be cuts in the funding of this approach if it didn’t work. But what actually happened?

Not much changed in the funding for or the definition of the program.

Raise your hands if you’ve been involved in a study where the same thing happened. Great work, little change.

Funding for family preservation continued, even grew a bit. And there was little debate reflecting our careful, rigorous evaluation work. People kept using the same models, with limited adjustment. Why did so few people listen to this careful, rigorous work? Why did so little change?

In hindsight, I think we failed to get close. We took a rigorous scientific approach, but we ignored the emotional conflict at the heart of child welfare: the push and pull of two conflicting approaches, and the deep emotional connection each side had to its approach.

We asked the wrong questions and designed and implemented the wrong study.

We thought that people wanted to know the impact and that a program that did not show impact would be changed and improved.

But, thinking again about Ron’s pie, maybe this form of policy research was never going to be the driver of policy at the Congressional level. Or, frankly, on the ground at the state or community level.

We undervalued the history and the emotional commitment to this issue.

Could a rigorous study overtake centuries of emotional pull for keeping children with their families? That’s a bit like expecting Bambi to defeat Godzilla. Our hopes were crushed.

As my colleague Mark Courtney likes to say, social service programs are operated by true believers. They will not turn on a dime based on work we believe is scientifically rigorous.

Our work has to connect with them, with the emotional pull they feel, and with their commitment to the families they serve. Our somewhat distant scientific approach did not provide the types of information likely to be acted upon. This well-designed and well-implemented study was no match for the emotional pull.

The number of children entering care remained high following the study. It began to drop a few years later, though there is little evidence that that was because of improved family preservation services.

So, my story ends without the impact we all wished for. Now, perhaps we get our second chance, our policy mulligan, so to speak. A chance to forget a mistake and take another whack.

Why are we getting this chance? Sadly, because the number of children entering care has gone up again. Not at an alarming rate—but enough to push the focus back to family preservation.

Last year’s Family First Prevention Services Act opened up the potential for massive new funding of family preservation services. This act, in some ways, is a dream for those of us who are passionate about effectiveness research as well as those who are passionate about family preservation. On the program side, it again supports family preservation services. It provides, for the first time ever, the use of federal entitlement dollars for services other than foster care, moving dollars from foster care support to family preservation. This funding could dwarf the previous funding for these services.

On the research side, it requires that the new funding pay only for evidenced-based programs. And it established a clearinghouse to review research on programmatic approaches. The federal government will reimburse states for some of the cost of evidence-based programs to families who are “candidates” for foster care. Other approaches will not be allowed.

Not everyone is happy. There are concerns that there is not enough evidence to build on, that it is the wrong evidence, that it is not built for the specific situations faced in child welfare. Administrators have spent years building their own family preservation programs. Many of those efforts will not be supported by federal dollars because they have not been rigorously evaluated. Program operators want help now, and they want it to tie into what they have become emotionally invested in.

It will, frankly, take years for the titration of evidence in this arena. Very few programs have been rigorously tested in actual child welfare settings. And many that are evidence based do not align with the realities of the child welfare system.

I share some of the concerns of these administrators.

Our scientific and rigorous efforts move slowly. I think our former approach to evaluation was a bit like 19th-century photography. We asked programs to hold still for long periods so that we could capture what they were doing.

Those who are emotionally invested in preserving families do not feel they can wait.

I think back to my experience with the family preservation evaluation, and I wonder: How we can approach this new situation with a better understanding of the history and emotional valence within child welfare policy?

I believe we can do better this time around. We don’t have to fail. We can have more impact. What if, this time, we met the field where it is and embraced the emotional aspects of policymaking? What if we recognized more of the history? What if we help those on the ground put together the pieces?

If we want policy research to have more than a 1-percent role, if we want to grow our impact, we have to do the groundwork. It’s too important to keep doing the same thing.

Maybe embracing the emotional investment people have can actually help us grow our piece of the pie.

I’d like to close with some recommendations.

First, let’s spend more time embracing those who are emotionally invested. What buttons does policy push, for all sides? What information would they like to see, and what would they possibly use? What will they keep doing no matter what? Let’s understand what they are unlikely to give up on given their emotional investment.

Second, let’s understand the history of the issue and how that relates to the emotions at work. How long has the approach been around? How has it changed? Who’s invested and why?

Third, let’s work less to assess programs and more to improve the programs people are invested in. That probably means conducting more formative evaluation and focusing on program improvement work and less on summative impact evaluation.

This can still be rigorous and scientific work, using new data analytics and rapid-cycle evaluation methods to give real-time information to those on the ground. We can communicate earlier and more frequently with clients, advocates, and program operators and understand the emotions behind their drive to preserve families. This recognizes that people are emotionally invested, but they may improve the levers that help them get to where they are trying to go.

Finally, let’s continue to push on the use of evidence-based programs. Not just from the top down but from the bottom up. Top-down evidence building is appropriate where it matches the context and where people are truly ready to implement programs well.

Our field has learned a lot about the challenges in implementing evidence-based programs. There is a still a strong role for rigorous impact work, and I’m a big fan of that, but our portfolio of work should not overemphasize that set of questions. Let’s build from the bottom up as well to work with those who are emotionally invested. We can help them move the things they care about into the evidence base.

All of this requires that we get closer to the people invested and their emotions. Listening more and adapting our methods to questions that matter most to them. We need to be patient with the development of programs. Working hand in hand with administrators for years to develop them to the point that they may have a chance to clear the evidence-based hurdle. Understanding, improving, and building evidence together.

As advocates ourselves for evidence-based policy, we ourselves are emotionally invested in getting it right—and having an impact.

In family preservation, it is great to get a second chance on this important issue. And I hope my story resonates on other issues that you, my APPAM colleagues, struggle with daily in education, crime and justice, health reform, and other areas.

Let’s grow the effects we can have on policy and practice. Let’s engage. Let’s get closer. Let’s appreciate the emotions and history behind the issues. And let’s help those who are passionate do better in what they must do.

I see an additional benefit from getting closer. This work can bring together all the elements of APPAM: analysis and management, getting closer to each other. We can move away from the role of that 19th-century photographer I showed—distant, requiring stasis, nonadaptive—toward the role of engaged improvers of public programs. Maybe policy research in the 21st century will be more in real time, will be more unsettling, and runs the risk of many legitimate concerns.

Maybe will look a bit more like this?

How does this make you feel? Happy? Excited? Jarred? Uncomfortable?

I’m excited. The way we are doing our work is changing. There are new ways to have the impact I’ve always wanted to have. Let’s get ready for it.

Thank you!