Clinical care only accounts for a small part—an estimated 10 to 20 percent—of the contributing factors affecting population health. The rest is determined by social, behavioral, and environmental factors, such as education, housing, and income, which interact dynamically to affect the health and well-being of individuals and communities. These factors, which are sometimes called social determinants of health (SDOH), play such an outsized role in keeping people healthy that a growing number of leaders in the government, philanthropic, nonprofit, and private-sector health care communities believe it is critical for providers to play a role in addressing them.

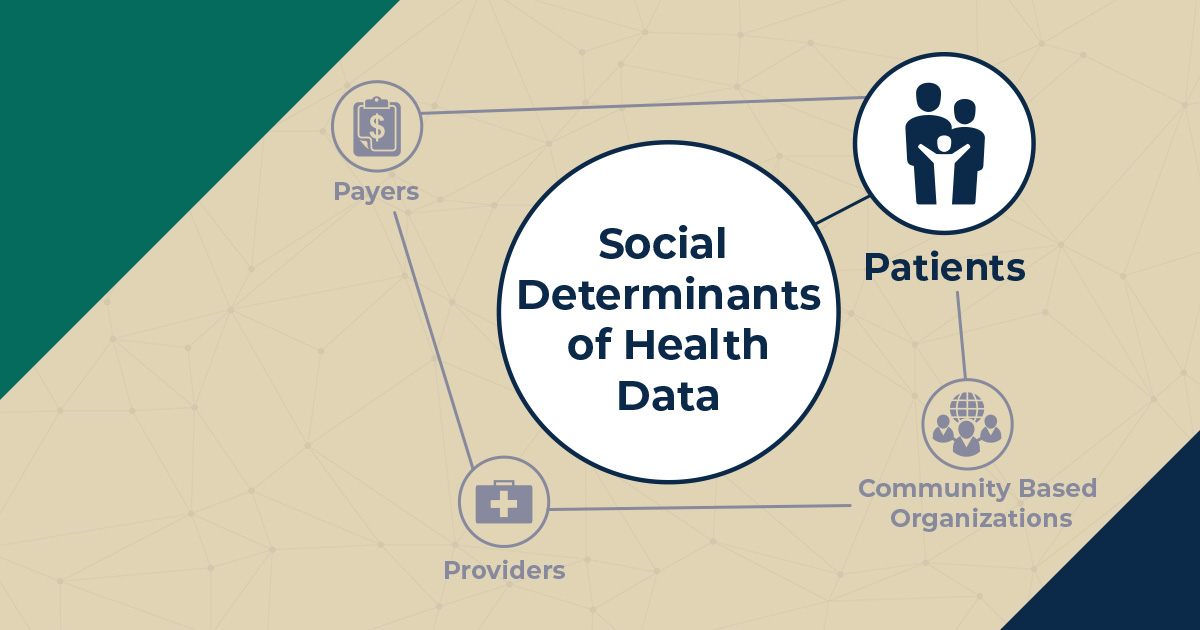

In order to improve patients’ overall health and well-being, we need better information about SDOH and the best methods of addressing them. This blog post is the first in a series that explores the needs, challenges, and opportunities in collecting and using SDOH data to drive decisions in health care delivery and payment. Each post will examine these questions from the perspective of a different stakeholder group involved in such decision making. Click here to read the post introducing this blog series.

We felt it was crucial to start this blog series where the data themselves begin: the patient.

What roles should patients play in the gathering and use of SDOH data?

Health care providers might already collect patients’ SDOH data, such as housing and employment status, through screening questions on a patient intake form or during a medical appointment with a clinician. Too often, patients are not engaged in deciding what providers ask and what providers do with the information they collect. Patients should be involved in all discussions regarding processes for collecting, using, sharing, and protecting SDOH data. Having them at the table for these discussions will ensure that processes are developed that respect the personal and sensitive nature of these data.

To ensure that patients feel empowered to make decisions regarding their own SDOH data, they should be engaged in shared decision making (SDM) to ensure that support offered and provided to them is person-centered, reflecting the person’s values and preferences. Rather than providers offering support solely based on a top-down screening tool—using scores on a standardized tool to determine a person’s unmet social needs—people should be asked what their concerns are and what support they want.

For example, a screening tool might determine that a patient is housing insecure and has an unmet housing need. However, that person might feel that living with friends is inconvenient but doesn’t rise to the level of a need. On the other hand, that same person might not meet the screening tool’s criteria for food insecure but might live in a food desert and be struggling to pay for and to access relatively expensive healthy foods or foods to accommodate dietary restrictions and might want help with that. Offering people support that they don’t perceive they need and not offering them support that they do perceive they need—offering them the wrong support—is not person-centered.

Similarly, patients should be engaged in SDM to ensure that they can make informed decisions regarding how to strike the right balance for themselves—one that reflects their preferences, based on a full understanding of the relative potential risks and benefits—between sharing and protecting their own data.

For example, some people are more private and would lean toward data protection, whereas others might feel that the benefits of having their data shared outweigh any concerns regarding privacy, so they would lean toward data sharing. In addition, people might feel comfortable with health and social services providers sharing information about some social risks (for example, food insecurity), but might feel more private about other social risks (for example, interpersonal violence at home), and wish to have that information more protected.

What barriers do patients face related to the gathering and use of SDOH data?

For one thing, patients historically have not been at the table for discussions regarding the collection and use of data in health care settings. As a result, many processes for SDOH data collection and use do not focus on what’s important to and meaningful for patients. In addition, because many of those processes are top-down, they do not encourage patients to participate in SDM to make sure that their data is gathered and used in ways that meet their preferences.

Some patients might also have difficulty expressing their needs and preferences. They might lack the necessary literacy or numeracy skills. They might struggle to cope with the reality of their circumstances. They might not trust health and social services providers, especially if they have a history of trauma. Or, on the flip side, they might feel afraid to challenge or disagree with providers.

Finally, patients are affected by structural barriers to data sharing. For example, health and social services providers might not have computer systems capable of exchanging data with other providers. Or, even if they are able to physically exchange data, the computer systems might define data elements differently, so the data that is shared doesn’t make sense to the provider receiving it. As a result, a patient might be faced with different providers who have different understandings of that patient’s needs or the services the patient has been offered or received, placing the burden of connecting the dots on the patient.

What opportunities are there for patients to advance their roles in the gathering and use of SDOH data?

A great way for patients to advance their roles in the gathering and use of SDOH data is to participate in patient and family advisory groups or as patient representatives on clinical advisory groups involved in developing processes for SDOH screening, navigation, data sharing, and data protection. Such participation will help ensure that the processes developed by health and social services providers are person-centered, focusing on what’s important to and meaningful for people.

Patients can also become cultural brokers in their communities, preparing others to engage in SDM with health and social services providers to address their social needs.

But other stakeholders—including community-based organizations, providers, and payers—need to do their part by engaging patients or advocacy representatives in discussions regarding collecting, using, sharing, and protecting SDOH data. Their involvement will ensure that data processes are person-centered and focus on what’s important to and meaningful for patients. Engaging patients in discussions about their data will help build the collaborative relationships necessary to engage in effective SDM and promote the improvements in quality, costs, and outcomes that all stakeholders want to achieve.

Read other posts in this series:

- To Address the Social Determinants of Health, Start with the Data

- The Power of a Data-Informed Partnership: Working with Community-Based Organizations to Address Social Determinants of Health

- Prescribing Social Services: Leveraging Data to Diagnose and Treat the Social Determinants That Affect Health

- In Pursuit of Value: How Payers Can Leverage Social Determinants of Health Data to Improve Outcomes